Case study 1[1]:

Tutelage

Irene K, 19 years old, left her parent’s home at the age of 16. At first, she lived on the streets alone, later on with a petty dealer and also took drugs herself. When she got pregnant from him, she separated from him, stopped taking drugs and looked for and found shelter with an NGO for sheltered living. There, she had to prove her ability to live independently in order to be granted a council flat later on. To that end, she had to meet up with her counselor regularly to prove her reliability, which turned out to be difficult:

She rarely kept appointments and behaved in a dismissive way towards her counselor. Her counselor found her to be very difficult, and not only doubted her ability to live independently but also thought Irene should give up the baby for adoption as she wouldn’t be able to take on that sort of responsibility.

Their relationship deteriorated and the question arose whether Irene could be kept among the NGS’s clients and whether she could really be assigned a council flat. Because of the unborn child, youth welfare services were contacted.

The intern who reported the case in a workshop did not work there anymore. A few months later she told us that she had met a colleague from that NGO, who said that everything has changed entirely regarding Irene: she has thrived, would be moving into her council flat soon and was thought to have everything under control.

Coincidentially, because her first counselor left for maternity leave herself, Irene was assigned another counselor. This new counselor was impressed upon reading Irene’s case description that this young woman broke away from drugs, her boyfriend and the street all by herself and obviously had not relapsed, and told Irene so during their first meeting. From there on, there have been no more difficulties with Irene.

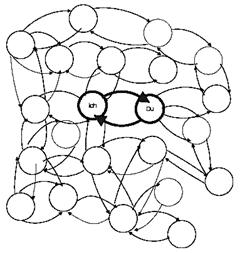

Figure 1: The fundamental feedback loop

Analysis in the workshop resulted in the conclusion that, probably, Irene was entangled in a similar interactional pattern with her first counselor as with her parents at the time of leaving home, and that change could only occur when a person in relationship with her could acknowledge her achievements.

Our „diagnostic“ approach in the Vienna School of Systemic Social Work aims at interpreting behaviour resulting in critical case courses as feedback loops of negative reactions:

If the daughter tries

- to withdraw and

- if the parents react with criticism,

- the daughter will then try to withdraw from this criticism

- and if the parents react with criticism again,

then, in this case, such a feedback loop has emerged. This loop can be seen as a script in which behaviour has become predictable because it mutually conditions and causes each other.

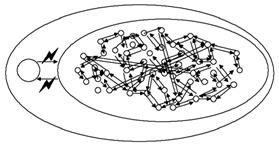

Figure 2: Outsider and society

If this pattern is recognized and if these mutual defensive attitudes can be found, one can deduct what can be done from the social workers’ side to achieve change. Social workers’ behaviour or that of the social environment of the indicated client respectively is here seen as co-constitutive part of the problem: Neither the daughter’s behaviour is independent and uninfluencable nor that of the parents, but both are a reaction to the other.

This is an example of a fundamental feedback loop.

In a simplified way, and explained along a relationship of two persons: each action of person A has an effect on person B – and on his/her actions. These, in turn, retroact on person A and his/her actions. Via the detour of the environment each action reacts upon itself.

And this repercussion we call feedback.

It can amplify interaction – this we call positive feedback, or attenuate interaction, which we call negative feedback. This principle of interdependence is the most fundamental basis of today’s systemic thinking, and only on the basis of the principle of feedback are we able to understand and describe autopoiesis and circularity.

We owe the principle of feedback to cybernetics: In the 40s of the past century William Ross Ashby (cf. Ashby:1964) built some small mechanical machines that were linked in a way that each change on one machine influenced all other machines as well. And behold, after some time of unordered change, the combination of machines started to achieve a state of equilibrium, and reacted to influences from the outside in a way to regain this equilibrium. Deviations were encountered in a neutralizing way. This procedure he called ‚negative feedback’. In the same way, he named another procedure, which could also happen, positive feedback: when a change in the system led the system to deviate more and more from its equilibrium – which, unchecked, would certainly lead to some form of catastrophe.

The mental research institute’s team in Palo Alto, whose most famous author was Paul Watzlawick, illustrated it in the way we still do: In a circle, in which two or more ways of behaviour mutally cause each other; either amplifying or attenuating (cf. Watzlawick: 2011). They deducted a perspective which assumes that disorders in human coexistence are always homostatic or escalating self-preserving cycles of interaction which consist of the participants wanting to change something in the interaction.

The earliest therapies deduced from this principle were the so called paradoxical interventions which aimed at rendering the attempt of change absurd by adding a mandate, thereby achieving a breakdown of the paradoxical fight for change.

You can find many examples for such interventions in Watzlawick’s ‚Human Communication: 2011’ and a second book, ‚Solutions: 2008’, in Selvini-Palazzoli’s ‚Paradox and Antiparadox: 1977’ and also in Thomas Weiss’ book ‚Family therapy without family: 1989’.

For interactional systems, Watzlawick’s proposition is valid that non-communication is not possible, and furthermore, that they consist of mutually circular causal actions:

Each action has an impact on its environment and therefore on actions in this environment. And these actions again retroact on the person who has started the original action, and that person’s further actions. And hence we have come full circle, which in simpler cases is called feedback and in more complex cases is called circularity.

Now we only have to understand how self-preserving or even self-amplifying developments emerge.

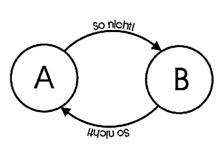

This can be illustrated with the help of the example above:

- If Irene struggles against tutelage by withdrawing herself; and

- if her parents and later on the social worker of the NGO „Sheltered Living“ interpret her attempts of withdrawal as lack of responsibility and want to spoon-feed her even more,

then, this results in an escalating system of mutually escalating actions. And the non-predictability of systems reactions recedes into the background, because some form of „sense“ has emerged and the participants of this communication will react in the same or similar ways to the same or similar actions. This is the manner in which such structures become relatively predictable.

It is important, however, to remain aware that this is not a form of static suchness, but a form of self-reproduction, that means that a seemingly stable situation is constantly reenacted through a specific interaction among the participants.

We call relationships that consist of a constant fight of all participants for change of the relationship dysfunctional relationships or vicious circles.

Figure three: The problem cycle

And, naturally, all actions seen as part of this circle cannot lead to change.

To understand circularity in social interactions, you have to disengage yourself from the conventional way of thinking, in which communication is only seen as „intended message“. Circularity can only be understood if one abides by the early communications theoreticans as Watzlawick or Bateson (cf., for example 1985), and includes everything into the examination that exists between humans altogether.

If a person loses their job, this is a message to him/her on the part of the employer, if someone receives the breadline, this is a message on the part of politics, and can also be seen as a message from society:

- From now on, we only help you via taxes.

- We let politicians decide what you should be able to afford, and, especially, what you shouldn’t.

(I would interpret the fact, that someone who wants to help privately has very little legal room to do so in a way that society in its politically elected whole or majority thinks that we should not give away a bigger share of our taxes. If someone receives something in private, s/he shouldn’t get it additionally through the breadline.)

If someone loses their flat, this is a message from his/her surroundings that s/he is not granted shelter anymore under the given circumstances: The behaviour of the affected person plays a major role, and additionally, as message to person(s) who have a flat to let: Factors like what a flat looks like, smells like and sounds, also belong to a person’s behaviour. And whether someone pays rent or not is also counted among a person’s communication.

For the sake of comprehensiveness I would like to point out that all of our functioning interaction in society also consists of – often complex – circular loops, for example, the baker bakes bread because it is bought and bread is bought because he bakes it, the same way as other societal functions are carried out as long as there are reactions that effectuate them.

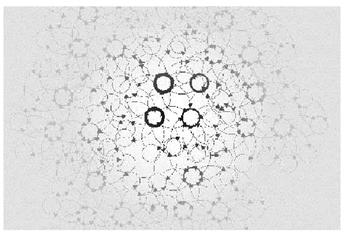

These circular loops are often very complex so that they cannot be perceived in every detail, but if somewhere things are escalating, the central participants are made salient through the intensity of the reciprocal action and one can observe them.

Figure 4: Escalating systems in society are salient

Case study 2

The stronger one has his say[2]

In my role as supervisor, I once got trapped in a remarkable case concerning meta communication: There was an Albanian family whose son was doing poorly at school. The teacher asked the parents to come, and when they did come swiftly, the father threatened to burn the teacher’s house if the teacher caused their son further trouble. The director, who contacted the parents next, was also threatened. For some reason, the case was brought to the attention of the local school authority, who asked for police protection when the father threatened to torch the building of that authority.

And here was the trap: in a supervision group, we tried to find a solution together how we could pay the gentleman from Albania sufficient respect so that we could deal with him cooperatively, so that he would also cooperate with us.

But the story took a different course: the police got annoyed with the man because of whom they had to protect a large building, and arrested him for a few days due to dangerous threats. From that moment on, the Albanian was the most cooperative man the responsible social worker has ever seen, and did everything that was suggested in order to help his son. I hope noone believes now that the man had been malicious! I rather tend to think that in his home culture it was customary that the stronger one decided what was going to happen, an therefore it was necessary to find out who was the stronger one.

Theses:

A priori:

This is not the true description of reality. Each description of reality has its justification as long as it delights somebody. I find mine quite practical when dealing with social pheonomena of every kind. But I also think that it can describe each perceivable phenomenon altogether. It is logical and consistent and can depict each and every conceivable circumstance. |

The theses:

- Whatever exists in the world, does not exist due to some (historical) cause but foremost because it reproduces itself constantly in the course of a reciprocal action with its environment. This means that there are no things that were created at some point and continue their existence without self-reproduction. However, there are things, that only emerge in the course of a reciprocal action and keep existing in one. Each phenomenon in the world can be described in the scope of such a reciprocal action.

- One can divide the world into arbitrary entities in order to study such reciprocal actions: one can examine the reciprocal action between two humans (one has to factor in the reciprocal action of this subsystem with the world, however), the reciprocal action of one human with the rest of the world, the reciprocal action between humans and organisations, in short, everything where effects can be exchanged.

- Basically, all parts of the world have to be factored in and have to be reflected in regard with the question which more or less relevant role they play through their doing or their non-doing in the course of a reciprocal action. Also the effect of the observer, describer, reflector or analysor of a reciprocal action on the examined reciprocal action needs to be taken into account.

- Reciprocal actions do not happen due to intentions of the conscious and the unconscious kind, also not due to emotions or the like, but due to the exchange of effects (Showing emotions can trigger an effect). They do not prerequisite thinking or consciousness of the participating elements (i.e., an unconsicous person lying on the street will in most cases have an effect and thereby become part of a reciprocal action).

- The attempt at eliminating an issue (by whoever – including myself) can either cause the issue to dissappear or to continue its existence. If something shall be eliminated and still continues to exist, one should reckon that by the very attempt at elimination one contributes to its existence. This means, among other things, that one can assume that things that have been in existence for a while, will defend themselves against attempts at eliminating them. This means that rejection or the attempt at elimination is usually not causing change (except if one uses more forceful measures than have been tried previously).

- Because the world exists due to reciprocal actions and because I am one of the participants, this results in the fact that the only way I can achieve change is by showing a changed behaviour. Changes in others can only be caused by the effects of my behaviour.

- As we cannot recognise the mechanisms of the participating elements, but only the self-preserving reciprocal actions, it is basically not possible to predict anything more than repetition, escalation, or change. The direction of change is basically not predictable, i.e., what changes in which way due to a change in ourselves is not predictable. This means, we might be able to break a vicious circle but we cannot govern which new reciprocal actions will emerge.

The fact that one can deduct a highly effective diagnostic instrument for social relationships from the principle of feedback, but no all-time valid procedures how a counselor should behave when encountering a specific social phenomenon, might be one reason why this way of perceiving things has not become common knowledge in social work.

DeShazer’s and Berg’s (2009) solution-oriented approach can be deducted from this principle, but has proclaimed the solution-orientation its absolute maxim, so that it is more easily implemented as a rule of conduct. Solution-orientation really only is a method that is useful in many cases (in those in which participants of the problem can think and perceive in a problem-oriented way), but not in others. One can get stuck as easily using a solution-oriented approach as when using another method, and in that case the proposition formulated by DeShazer himself comes into force: If something does not work, do something different!

In cases like the one above, the game will be continued as long as someone does something the father understands as weakness: this is the very motivation for him to continue his fight. He will most likely not view positive connotation and miracle questions relevant for clarifying the relationship.

Looking at the reciprocal feedback loop can help us to perceive of which parts the „problem“game consists of, but from there on, not a recipe, but rather creativity is needed. And this does not consist of following a set of rules. It does not exclude them, but if it is narrowed downto them, it will fail.

Another reason for the fact that circular thinking has not really been accepted widely in social work is the fact that, normally, social workers work in the mandate of an institution that has certain ideas about how their clients should behave after having received assistance. If,at maximum, we can manage to break vicious circles, it is outside our control to promise exact results of our interventions. Circular thinking makes this fact very plain.

Case study 3:

The absolution of the refugees.

(Edith Ivancsits:2000)

Mrs. M (37 years old) arrived three weeks after the fatal car accident of her partner, Mr. R., together with her daughters Istia (16) and Mura (12) at the Caritas’ refugee home in Neudörfl. The family is originally from Bosnia and has lived in Austria for approximately five years. Mrs. M. and Istia, her daughter stemming from her first marriage, are Christians, Mura is a Muslim, like her father. Religious affiliation still plays a major role in Bosnia. Mrs. M.’s relationship with Mr. R. has never been endorsed by her family, and, on the other hand, Mrs. M. has never been in affectionate contact with her partner’s family.

Mrs. M. divorced her first husband shortly after the birth of her first daughter because he suffered from severe depressions, and she could not deal with that situation (according to her own explanations). Shortly afterwards, her first husband committed suicide. Approximately three years later, she came to know Mr. R.. When their joint daughter Mura was almost four years old, Mr. R. left his family in order to work as a foreign worker in Austria. During the turmoils of war Mr. R. had Mrs. M. and both girls come to Austria.

He was able to integrate himself here. He found work relatively easily, rented a small house and integrated himself in the local soccer association. So, when Mrs. M. arrived in Austria with her daughters, she was welcomed by a prepared, relatively secure social network. Two years later, Mrs. M. had to be taken in as patient at a psychiatric unit. Her diagnosis: „severe depression with danger of self-endangerment“. After a few weeks in hospital, Mrs. M. was sent home, but ever since she has been taking antidepressants on a daily basis.

Shortly after this incident, the family arrived at the refugee home, as their financial ground had suddenly disappeared. After Mr. R.’s death, several „helpers“ offered to support Mrs. M. (relatives, teachers, the parish, soccer friends of Mr. R.’s, Mr. R.’s working colleagues). Basically, these helpers organised Mr. R.’s funeral (including a translation of the body), collected money for the „poor“ children and thereby took everything out of Mrs. M.’s hands. In parts, Mrs. M. had no clue what had been arranged, how much the corpse’s translation had cost, whether her visa has been prolonged, etc. She said that she was told to keep calm and that everything will be done to her satisfaction.

It also was not she herself who approached the Caritas, but rather a friend who dropped her off there because Mr. R.’s brother and his family were also living in this home. They moved there in September 1997.

As the family is originally from Bosnia, Mrs. M. and her daughters received a visa until July 1997 according to §12. Mrs. M. had a family visa. Shortly before his death, Mr. R. took the applications for the visa’s renewal to the relevant authorities (in this case: the district commission of Mattersburg).

After Mr. R.’s death, the passports remained at the district commission. The social worker in charge was informed by the authorities that the family’s visa could not be prolonged because Mrs. M. stems from a part of Bosnia not occupied by Serbs. In this case, the homeward journey can be deemed acceptable for her and her two daughters, and they were granted two months to do so or else they would be deported.

Approximately two days after arriving at the refugee home, Mrs. M. felt a relatively large lump in her breast and informed a social worker about it. An application for health assistance was issued at the municipality and this was then passed on to the welfare department of the district commission.

According to law, health assistance can be granted to foreigners if this is necessary due to personal, family-related, or economic circumstances to prevent cases of social hardsip. In Mrs. M.’s case, health assistance was granted and she was taken to hospital, operated on two days later, and the lump in her breast turned out to be a malign tumor.

During Mrs. M.’s stay at the hospital, her sister in law, who also lives in the same refugee home (see above) took care of the girls.

The Caritas team in Neudörfl included Mrs. M. in all actions concerning her family. All measures were explained in detail to her and in parts delegated to her. The team wanted to offer professional help and did not want to take on the role of the private „helpers“.

The result of the supervision meeting:

Flight plays a major role in the discussed system as Mrs. M. has left behind her family (parents and siblings).

Refugees often experience a bad conscience towards those left behind. They often feel as traitors to their home country - which can lead to an exaggerated idealization of the native country or the attempt to mollify relatives at home with presents, etc.

When someone has a bad conscience, i.e. when s/he thinks s/he has incurred guilt, an „absolution“ is a possible approach to help.

In Mrs. M.’s case, one could say that she carries all of Bosnia’s misery within herself. Noone could blame her to have had it easy. She also suffered a lot, which means she does not have to make any more sacrifices. In her case, this would mean she is allowed to live.

As the director of the refugee home in Neudörfl is a former priest, Mrs. M. could receive her „absolution“ from him.

How has the case proceeded up until now?

As we are still in touch with the refugee home, we were allowed to continue observing the situation.

The director managed to voice Mrs. M.’s absolution in an intensive meeting with her:

„Mrs. M., you have lived the past few years in Austria, but you have suffered more than you probably would have in Bosnia. You have more than paid your debt, and you do not have to sacrifice yourself any more.“ (Those were his approximate words.)

Mrs. M. started to cry and wanted to be left alone. After two hours, she asked a social worker to come to her and, all of a sudden, she was able to talk about her fears and her grief.

She expressed a major wrath towards her mother, and also towards both of the men who have left her alone. Her old mother suddenly mutated from an ailing and needy woman into a kraken who has never let her daughter go. Mrs. M. also reported that both her partners had abused her and that Mr. R. has only shown interest in his biological daugther.

One day after this talk, Mrs. M. brewed good Bosnian coffee for the whole team (before then, there had been only filter coffee!), and said that she was doing fine at the moment. Unfortunately, from a medical point of view, this is not true. Mrs. M. has to undergo chemotherapy and radiotherapy and is suffering severely from side effects.

Mrs. M. and her daughters could not leave the country due to Mrs. M.’s cancer. The social worker contacted the foreign police at the district commission of Mattersburg regarding the newest developments in the case of Mrs. M. The responsible civil servant promised not to deport the family so that Mrs. M. can complete her vital therapies in Austria.

Every now and then, Istia and Muria talk about returning to their native country. At the moment, this is imaginable for them, on the condition that their mother recovers from her illness. But they definitely want to finish the ongoing year of schooling in Austria.

Ever since this talk, Mrs. M. talks more often about her feelings. She can accept her grief and rage now and she also shows a lot more commitment when planning her future. She is interested in clarifying her situation in terms of alien legislation. She knows that a deportation to Bosnia is realistic, but also does everything to be able to remain in Austria.

That means we could notice a remarkable change of behaviour in Mrs. M.. I have a feeling that Mrs. M. is taking on responsibility for her life again.

Theoretical comment

By W. Milowiz

Our thoughts when discussing the case were the following: When everyone wants to help while a person fights this with a depression and also on a physical level, this could be a vicious circle. We thought a relevant change in this system would be to view her suffering as important and valid, instead of trying to soothe it. And then there was the consideration whether it might be possible to direct her suffering despite the recognition of its meaningfulness towards another change.

Fortunately, thanks to reading many case studies in the literature of Milton H. Erickson and our own experience and some knowledge about different cultures, we were able to construe something that fit into the woman's imagery.

In the past few years, I have become very sensitive towards the question how a certain behaviour can mean different things to different people, and that humans who cannot understand each other due to this, often end up in a vicious circle.

Cultural differences definitely play a role. But there are also differences in the cultures of family A. and family B., in which, from a sociological viewpoint, one would not concede the smallest cultural difference. Who knows, for example, that in family X., one uses the phrase, "Such nonsense!" when one does not understand, and that in this family, it is customary to react to this phrase by explaining in more detail? I, for myself, tend to react rather aggressively in this case.

Recently, we talked about a situation at the social academy in which a woman from Serbia, who was sent by the family authorities with her children to a free, supervised family vacation on a farm and who constantly wanted to contribute something: pay something, take on work, etc. The counselors, however, wanted her to spend some freetime with her children. The poor woman became more and more nervous and more and more insecure, and later on also aggressive, until she finally completely withdrew. The only action she continued until the end of her vacation was to try to force money on her hosts.

I think many social workers know this tricky situation when people who have received some financial assistance because of their catastrophical situation - and again, these are often people with a migrational background - when these people want to present us with relatively expensive gifts. I am not sure whether in this instance it is about showing gratitude or about keeping the sham of equality, or whether it is a way of humouring someone who might be useful later on - maybe it is a little bit of everything - but the fact that something relevant is at work here is also shown by the fact that it is practically impossible not to accept these gifts. Maybe it would become possible if one could grasp their „real“ meaning as was obviously possible with the Bosnian woman described above.

I hope I have been able to tell you something new, although all of this is pretty old already.

In Vienna, we are always including this self-reproduction of problematic sitations when working systemically: if something exists for a longer time span, there must be a mechanism of how it preserves itself.

And therefore we understand our interventions in a way that they bring movement into gridlocked interactional patterns and thereby make change p ossible. We do this by bringing something into the system, something new that has not been there before. This new something has to be invented in each situation, there can be no rules about it, and this makes the application of this model of thought, though so simple, oftentimes difficult.

We also assume that people, as soon as they can move more freely again, find new and more productive ways of living together. This is the second difficult moment: to have faith that something meaningful happens although we cannot direct it.

And last but not least: introducing something new often means acting unconventionally. This is sometimes difficult to advocate: in front of oneself, one's colleagues, one's employers and the world. |